This is part two of three about culturally responsive teaching and learning with Otus. Part two discusses culturally responsive instruction.

In the first post of this series, we discussed how Otus can support educators in managing diverse classrooms. In this post, we will explore how culturally responsive instruction can bridge the complex relationship between learning and academic achievement in diverse classrooms.1

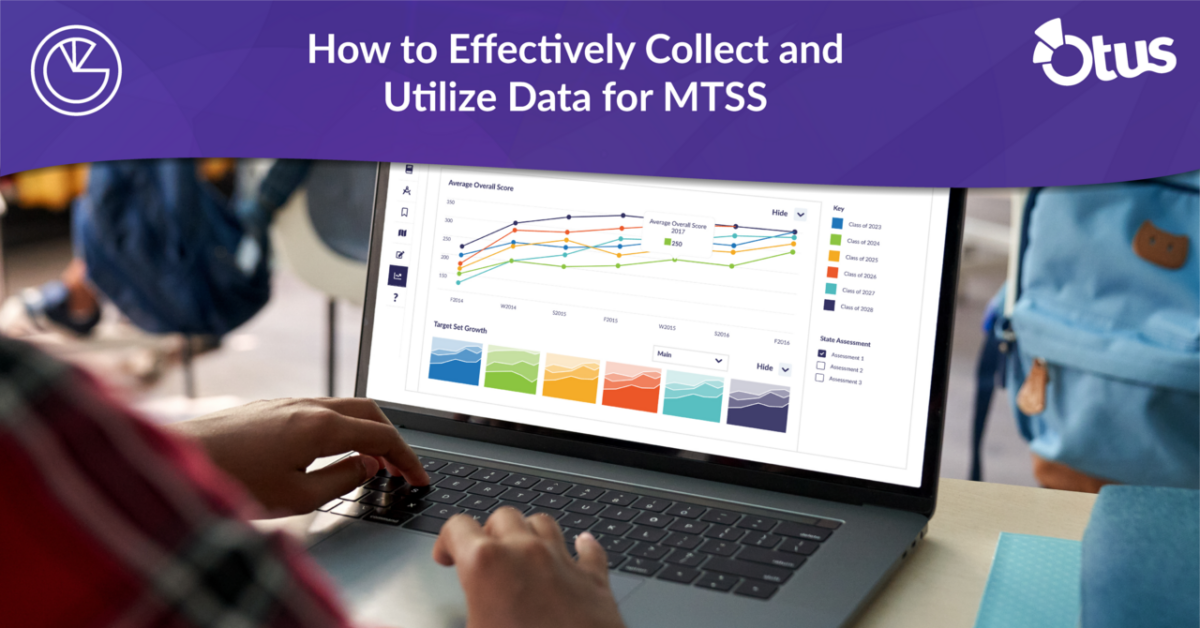

As 21st century educators, we often have disconnected sources of information to inform our understanding of student achievement and mastery. With Otus, teachers have a single platform to access all the information about social, cognitive, and academic development. This data speaks to the daily work of culturally responsive educators as they view learning as integrated rather than separate.2

Teachers can hold forth culturally responsive best practices when creating assessments for learning. Assessments can draw upon cultural beliefs and behaviors that emerge from family and community experiences. Once teachers recognize the dynamics of difference in student learning, they can author assessments to include real and hypothetical experiences. Educators can even use cultural knowledge to situate problems in relevant context like the example questions below:3

First-generation American Cesar Chavez was a civil rights, Latino, and farm labor activist who said, “Our language is the reflection of ourselves. A language is an exact reflection of the character and growth of its speakers.”

Q1: Why might Cesar Chavez say that language is an exact reflection of the character and growth of its speaker? Explain your thinking.

Q2: Suppose that in a fictional society, tensions in civil rights and farm labor did not exist. What would that society look like?4

Since culturally proficient schooling is dedicated to educating all students and using the student’s cultural backgrounds, language, and learning strategies to develop curricular and instructional resources, the framing of cultural differences in assessment can even provide evidence for changing the ways student performance and knowledge are assessed. As culture is defined in our classrooms, its ability to influence educational outcomes is likely to be enhanced as educators draw upon students’ community and home lives in the educational process.5

Accordingly, assessments and instructional resources can reflect multicultural perspectives and be assigned to entire classes, Flags (flexible student groupings based upon student engagement or proficiency data), and individual students within the platform. As learning occurs, teachers can use student data to inform instruction, view the impact of their culturally responsive planning and instruction in real time, and view results through Otus Analytics.6

Nevertheless, with the culture of schooling and learning top of mind, educators are able to create a rhythm, flow, and energy bridging the complex relationship between learning and academic achievement in diverse classrooms. By maximizing teaching and learning through a culturally responsive lens, we can continue to develop culturally responsive instruction and grow the foundation for education to be more individualized, robust, and comprehensive for all students in the school community.7

References

1. Randall B. Lindsey, Michelle Karns, and Keith Myatt, Culturally Proficient Education: An Asset-Based Response to Conditions of Poverty (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin, 2010).

2. Lindsey, Karns, and Myatt, Culturally Proficient Education; and Robert Dillon, “All Things Great and Small: 4 Ways to Build a Bridge Between Big and Little Data,” The Data Workout: How It’s Impacting Teaching and Learning (EdSurge Guide), Oct. 24, 2016, https://www.edsurge.com/news/2016-10-24-all-things-great-and-small-4-ways-to-build-a-bridge-between-data.

3. Lindsey, Karns, and Myatt, Culturally Proficient Education.

4. “Education of the Heart: Quotes By Cesar Chavez,” Cesar Chavez Foundation, accessed Nov. 18, 2016, http://www.chavezfoundation.org./_cms.php?mode=view&b_code=001008000000000&b_no=2197&page=1&field=&key=&n=1.

5. Carrie Rothstein-Fisch and Elise Trumbull, Managing Diverse Classrooms: How to Build on Students’ Cultural Strengths (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2008); and Renee Smith-Maddox, “Defining Culture as a Dimension of Academic Achievement: Implications for Culturally Responsive Curriculum, Instruction, and Assessment,” The Journal of Negro Education 67, no. 3 (1998): 302-17, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2668198.

6. Rothstein-Fisch and Trumbull, Managing Diverse Classrooms.

7. Ibid.; Lindsey, Karns, and Myatt, Culturally Proficient Education; and Dillon, “All Things Great and Small.”