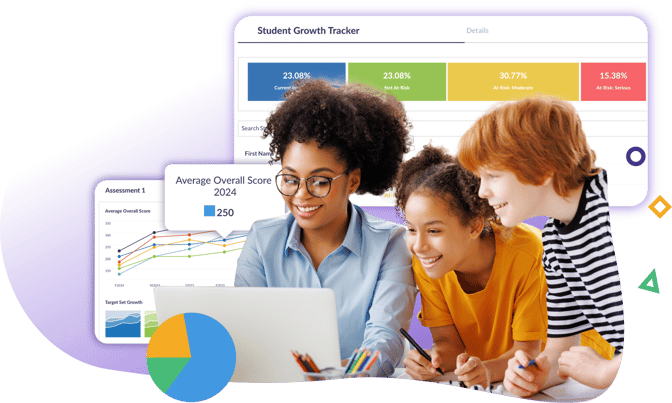

Insights and Tools That Drive Student Growth

Otus combines data, assessment, progress monitoring, and grading to maximize student performance and save educators time.

Save Time by Keeping Everything in One Place

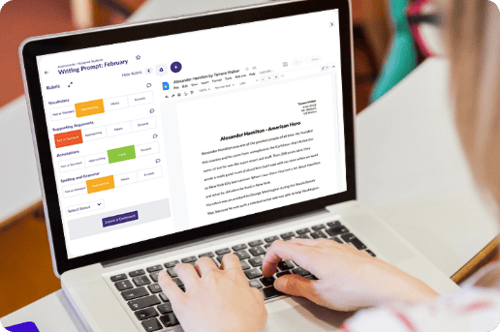

Assess Student Growth Your Way

Access engaging, standards-aligned assessments from leading K-12 programs or create your own. Whether formative or summative, assess with ease and share resources across teams.

A Gradebook for Every Grading System

Track progress toward learning standards with flexible grading, where scores flow seamlessly into the gradebook, providing real-time data and insights for educators to guide future instruction.

Bring Data Together for Insights on Student Performance

Create custom reports to analyze student performance on any external assessment side by side with teacher-administered assessments. Compare students' performance over time and use the data to make better informed district-level decisions.

Track Progress Towards Learning Goals

Create custom plans to track progress in academics, behavior, attendance, and more. From small groups to district-wide MTSS, ensure every student receives timely, targeted support.

See How Otus Works

Watch this video to learn how Otus helps educators make confident, informed decisions that drive student growth.

Otus Serves the Entire School Community

Solutions for Every School's Unique Needs

- Standards-Based Grading

- Data-Driven Decisions

- MTSS

- Portrait of a Graduate

- Common Assessments

- Family Engagement

- Early Literacy

Standards-Based Grading

Track progress toward learning standards and provide students with meaningful feedback that guides their growth.

Data-Driven Decisions

Use real-time data to inform instruction and make strategic decisions that improve student outcomes and drive district growth.

MTSS

Create targeted support plans to meet the academic, behavioral, and social-emotional needs of every student, ensuring no one is overlooked.

Portrait of a Graduate

Align instruction and initiatives with the skills students need for future success, tracking key competencies every step of the way.

Common Assessments

Use consistent assessments across classrooms to measure growth, validate learning, and align instruction with standards.

Family Engagement

Build strong family partnerships with real-time insights into student progress and success.

Early Literacy

Support early literacy with the right tools to ensure reading success for all.

Standards-Based Grading

Track progress toward learning standards and provide students with meaningful feedback that guides their growth.

Data-Driven Decisions

Use real-time data to inform instruction and make strategic decisions that improve student outcomes and drive district growth.

MTSS

Create targeted support plans to meet the academic, behavioral, and social-emotional needs of every student, ensuring no one is overlooked.

Portrait of a Graduate

Align instruction and initiatives with the skills students need for future success, tracking key competencies every step of the way.

Common Assessments

Use consistent assessments across classrooms to measure growth, validate learning, and align instruction with standards.

Family Engagement

Build strong family partnerships with real-time insights into student progress and success.

Early Literacy

Support early literacy with the right tools to ensure reading success for all.

What K-12 Leaders Are Saying About Otus

"We've never had a platform that encompasses everything—from testing to data, progress monitoring, and MTSS—all in one place, with a complete student profile. With our previous platform, teacher engagement dropped to just 10%, so we knew we needed a solution that would reengage teachers and make student data easy to access and use."

Millie Boykin

Director of School Improvement

Bulloch County Schools (GA)

“We really needed a data system that was different from what our Student Information System would provide – a way to look at students more holistically including their past and present data. I started using the plans in Otus last year and this works really well for academic tracking. This year, I’ve taken it to my entire intervention team.”

Jessica Conn

MTSS Coordinator

Maureen Joy Charter School (NC)

“We have a very unique competency-based system for assessment – a mash-up of competency, standards, mastery, and traditional. It was very difficult to find a tool and gradebook to support how we do things, and Otus filled every need we had.”

Camp

Head of Teaching and Learning

New England Innovation Academy (MA)

“What we love about Otus is we can create any type of assessment — formative, summative, rubric. I can also create any type of question. We had a seventh-grade ELA assessment where the learning standard was to match a type of media to an article. I was able to upload a podcast in Otus and add a nonfiction article that our students were able to toggle between.”

Vivian May

Secondary Instructional Coach

Marion Country Schools (KY)

“I love the simplicity of Otus! From the beginning, Otus stood out as being clean and very easy to navigate compared to our last system and other systems we were piloting. The fact that we could collaborate and share out resources on one platform made things so much easier.”

Lisa Wardle

Hemet Unified School District (CA)

“With just a few clicks on Otus, I can get the full picture of every student. It’s data that I can truly use instead of perusing through charts that have been formed a week after the fact. The immediate nature of the actionable data is what makes it even more powerful.”

Trevor Johnson

Second-Grade Teacher and Technology Advisor

Santa Rosa Academy (CA)

“I wanted to find a tool that could ground the data, but, more importantly, create something that’s user-friendly for teachers and students. Our students can really own their metrics and their journey, and see the relationship between goal-setting and the progress that they’ve made. With Otus, you’re going to see a more invested student, and they’re going to understand the relevance. It’s one of the best data tools to support Portrait of a Graduate.”

Scott Carr

College and Career Readiness Consultant

CESA 2 (WI)

“We had a lot of teachers using different platforms and parents were getting confused. Utilizing Otus helped us to really streamline that so that there was one single system to help their student navigate learning.”

Lexi Robinson

Instructional Technology Coordinator

North Shore School District 112 (IL)

Implementing EdTech Shouldn't Be a Headache

Partner with experts who truly understand education—our team of former educators provides personalized guidance to make implementation seamless, allowing your school to focus on student success.

Discover What Otus Can Do for Your School

.webp?width=655&height=858&name=tsp-CT-finalist-25%20(2).webp)

.png?width=250&height=347&name=WinnerBadge_800px%20(1).png)

.png?width=250&height=206&name=ISTEBOS_2024_Winner_Dark%20(1).png)

.png?width=250&height=240&name=EdTech_Breakthrough_Awards_2024-Otus%20(1).png)

.png?width=250&height=250&name=Stevies24_Bronze_Winner_Badge%20(1).png)

.png?width=250&height=141&name=CODiE-Winner-Logo-Black-2023%20(1).png)

.png?width=250&height=214&name=5%20(1).png)

.png?width=230&height=197&name=SmartBrief-on-EdTech-Readers-Choice-Award-Winner-2023%20(1).png)

.png?width=230&height=197&name=Globee-Awards-Gold-Winner-2023%20(1).png)